Uso de la API de WebVR

La API WebVR es una fantástica adición al kit de herramientas del desarrollador web, permitiendo que las escenas de WebGL sean presentadas en pantallas de realidad virtual como el Oculus Rift y HTC Vive. Pero, ¿cómo empezar a desarrollar aplicaciones VR para la Web? Este artículo le guiará a través de los fundamentos.

Nota: La versión más estable de la API de WebVR (1.1) se ha implementado recientemente en Firefox 55 (Windows en versión de lanzamiento y Mac OS X sólo en Nightly) y también está disponible en Chrome cuando se usa con hardware de Google Daydream. También hay una evolución posterior de la especificación 2.0, pero esto está en una etapa temprana ahora mismo. Puede encontrar información sobre el estado más reciente de las especificaciones en WebVR Spec Version List.

Empezando

Para empezar, necesita:

- Soporte de hardware VR.

- La opción más barata es utilizar un dispositivo móvil, compatible con el navegador y el dispositivo montado (por ejemplo, Google Cardboard). Esto no será una experiencia tan buena como el hardware dedicado, pero no necesitará comprar una computadora potente o una pantalla VR dedicada.

- El hardware dedicado puede ser costoso, pero proporciona una experiencia mejor. El hardware más compatible con WebVR en este momento es el HTC VIVE, y The Oculus Rift. La primera página de webvr.info tiene alguna otra información útil sobre hardware disponible y qué navegador los soporta.

- Una computadora lo suficientemente potente para manejar la representación / visualización de escenas VR usando su hardware VR dedicado, si es necesario. Para darle una idea de lo que usted necesita, mire la guía relevante para el VR que usted está comprando ( p. ej.VIVE READY Computers).

- Se ha instalado un navegador de soporte: el último Firefox Nightly o Chrome son sus mejores opciones ahora, en el escritorio o móvil.

Una vez que tengas todo montado, puedes probar si tu configuración funciona con WebVR yendo a nuestro simple A-Frame demo, y ver si la escena se procesa y si puede entrar en el modo de visualización VR pulsando el botón en la parte inferior derecha.

A-Frame es de lejos la mejor opción si desea crear una escena 3D compatible con WebVR rápidamente, sin necesidad de entender un montón de código nuevo de JavaScript. Sin embargo, no te enseña cómo funciona la API WebVR en bruto, y esto es lo que veremos a continuación.

Introduccion a nuestra demostración

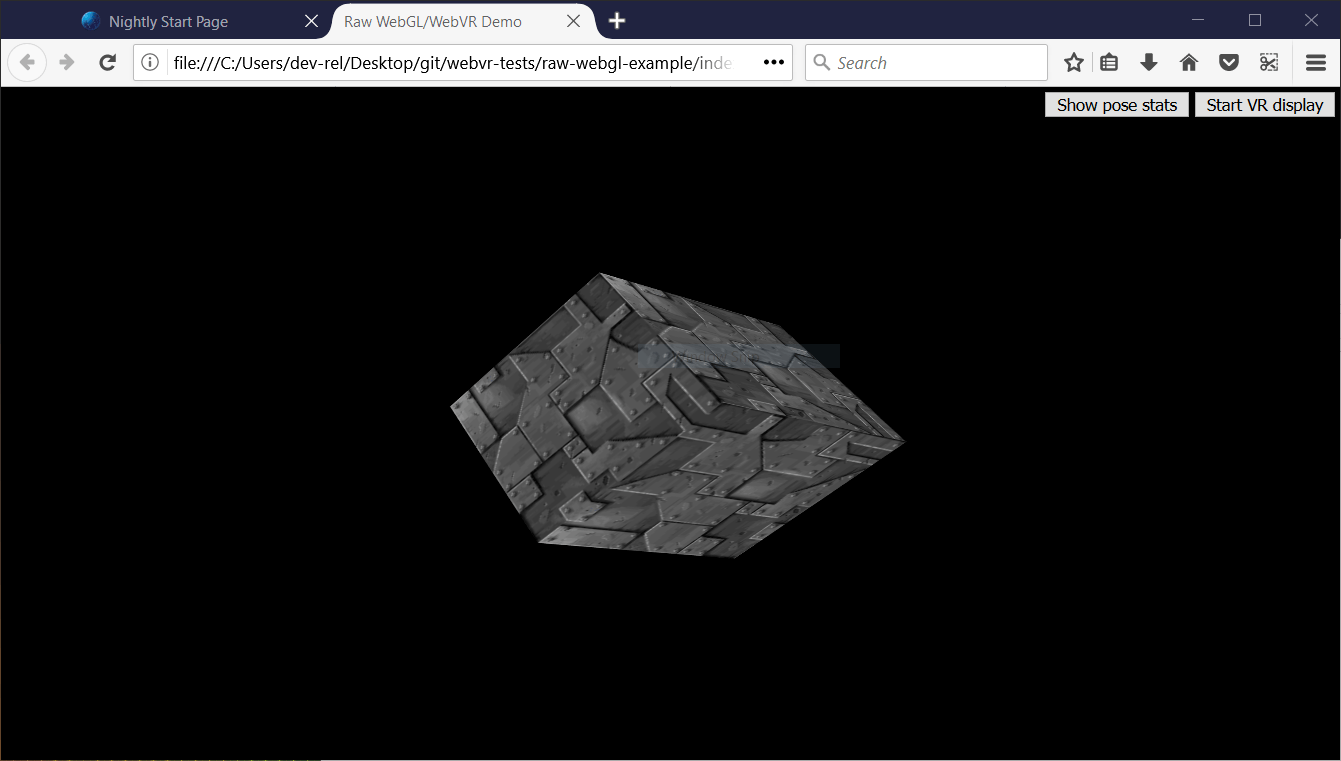

Para ilustrar cómo funciona la API de WebVR, estudiaremos nuestro ejemplo raw-webgl-example, que se parece un poco a esto:

Nota: Puedes encontrar el código fuente de nuestra demo en GitHub, y verlo en vivotambién.

Nota: Si WebVR no funciona en su navegador, es posible que deba asegurarse de que se está ejecutando a través de su tarjeta gráfica. Por ejemplo, para las tarjetas NVIDIA, si el panel de control de NVIDIA se ha configurado correctamente, habrá una opción de menú contextual disponible - haga clic con el botón derecho del ratón en Firefox y seleccione Ejecutar con procesador gráfico > Procesador NVIDIA de alto rendimiento.

Nuestra demo presenta el santo grial de las demostraciones de WebGL - un cubo 3D giratorio. Hemos implementado esto usando raw WebGL API código. No enseñaremos ningún JavaScript básico o WebGL, solo las partes de WebVR.

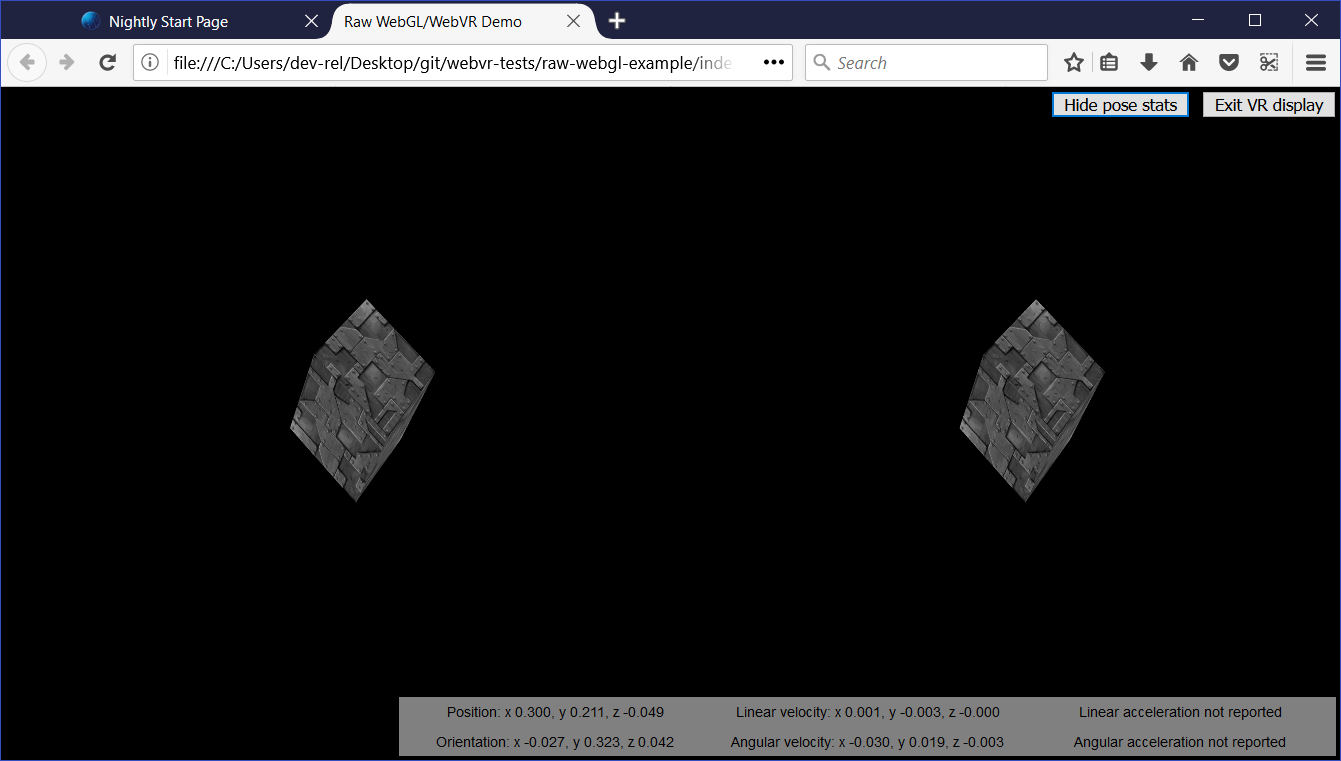

Nuestra demo también cuenta con:

- Un botón para iniciar (y detener) la presentación de nuestra escena en la pantalla VR.

- Un botón para mostrar (y ocultar) los datos de pose VR, es decir, la posición y orientación del auricular, actualizados en tiempo real.

Cuando miras a través del código fuente denuestro archivo JavaScript principal de demostraciones , puede encontrar fácilmente las partes específicas de WebVR buscando la cadena "WebVR" en comentarios anteriores.

Nota: Para obtener más información sobre JavaScript básico y WebGL, consulte nuestro material de aprendizaje JavaScrip , y nuestro WebGL Tutorial.

¿Como funciona?

En este punto, veamos cómo funcionan las partes WebVR del código.

Una típica (simple) aplicación WebVR funciona de esta manera:

Navigator.getVRDisplays()(en-US) se utiliza para obtener una referencia a la visualización VR.VRDisplay.requestPresent()(en-US) se utiliza para iniciar la presentación en la pantalla VR.- WebVR's dedicado

VRDisplay.requestAnimationFrame()(en-US) se utiliza para ejecutar el bucle de representación de la aplicación a la velocidad de actualización correcta para la pantalla. - Dentro del bucle de procesamiento, se capturan los datos necesarios para mostrar el marco actual (

VRDisplay.getFrameData()(en-US)), dibuja la escena visualizada dos veces - una vez para la vista en cada ojo - luego envia la vista renderizada a la pantalla para mostrar al usuario a través de (VRDisplay.submitFrame()(en-US)).

En las secciones siguientes veremos en detalle nuestra demostración raw-webgl y veremos dónde se utilizan exactamente las características anteriores.

Comenzando con algunas variables

El primer código relacionado con WebVR que encontrarás es el siguiente bloque:

// WebVR variables

var frameData = new VRFrameData();

var vrDisplay;

var btn = document.querySelector(".stop-start");

var normalSceneFrame;

var vrSceneFrame;

var poseStatsBtn = document.querySelector(".pose-stats");

var poseStatsSection = document.querySelector("section");

poseStatsSection.style.visibility = "hidden"; // hide it initially

var posStats = document.querySelector(".pos");

var orientStats = document.querySelector(".orient");

var linVelStats = document.querySelector(".lin-vel");

var linAccStats = document.querySelector(".lin-acc");

var angVelStats = document.querySelector(".ang-vel");

var angAccStats = document.querySelector(".ang-acc");

var poseStatsDisplayed = false;

Vamos a explicar estos brevemente :

frameDatacontains aVRFrameData(en-US) objeto, creado con elVRFrameData()(en-US) constructor. Esto es inicialmente vacío, pero contendrá más adelante los datos requeridos para rendir cada marco para mostrar en la exhibición de VR, actualizado constantemente mientras que se ejecuta el ciclo de la representación.vrDisplaycomienza sin inicializarse, pero más adelante se realizará una referencia a nuestro auricular VR (VRDisplay(en-US) — el objeto de control central de la API).btnyposeStatsBtnmantenga referencias a los dos botones que estamos usando para controlar nuestra aplicación.normalSceneFrameyvrSceneFrameno iniciados, pero más adelante contendrán referencias aWindow.requestAnimationFrame()yVRDisplay.requestAnimationFrame()(en-US) llamadas - esto iniciará el funcionamiento de un bucle de renderizado normal, y un bucle de renderización WebVR especial; explicaremos la diferencia entre estos dos más adelante.- Las otras variables almacenan referencias a diferentes partes del cuadro de visualización de datos de pose de VR, que se puede ver en la esquina inferior derecha de la interfaz de usuario.

Cómo obtener una referencia a nuestra pantalla VR

Una de las principales funciones dentro de nuestro código es start () - ejecutamos esta función cuando el cuerpo ha terminado de cargar:

// start

//

// Called when the body has loaded is created to get the ball rolling.

document.body.onload = start;

Para empezar, start() recupera un contexto de WebGL para usarlo para renderizar gráficos 3D <canvas> elemento en our HTML. A continuación verificamos si la gl contexto está disponible — si es así, ejecutamos una serie de funciones para configurar la escena para su visualización.

function start() {

canvas = document.getElementById("glcanvas");

initWebGL(canvas); // Initialize the GL context

// WebGL setup code here

Next, we start the process of actually rendering the scene onto the canvas, by setting the canvas to fill the entire browser viewport, and running the rendering loop (drawScene()) for the first time. This is the non-WebVR — normal — rendering loop.

// draw the scene normally, without WebVR - for those who don't have it and want to see the scene in their browser

canvas.width = window.innerWidth;

canvas.height = window.innerHeight;

drawScene();

Now onto our first WebVR-specific code. First of all, we check to see if Navigator.getVRDisplays (en-US) exists — this is the entry point into the API, and therefore good basic feature detection for WebVR. You'll see at the end of the block (inside the else clause) that if this doesn't exist, we log a message to indicate that WebVR 1.1 isn't supported by the browser.

// WebVR: Check to see if WebVR is supported

if(navigator.getVRDisplays) {

console.log('WebVR 1.1 supported');

Inside our if() { ... } block, we run the Navigator.getVRDisplays() (en-US) function. This returns a promise, which is fulfilled with an array containing all the VR display devices connected to the computer. If none are connected, the array will be empty.

// Then get the displays attached to the computer

navigator.getVRDisplays().then(function(displays) {

Inside the promise then() block, we check whether the array length is more than 0; if so, we set the value of our vrDisplay variable to the 0 index item inside the array. vrDisplay now contains a VRDisplay (en-US) object representing our connected display!

// If a display is available, use it to present the scene

if(displays.length > 0) {

vrDisplay = displays[0];

console.log('Display found');

Nota: Es poco probable que tenga varias pantallas VR conectadas a su computadora, y esto es sólo una demostración simple, por lo que esto lo hará por ahora.

Starting and stopping the VR presentation

Now we have a VRDisplay (en-US) object, we can use it do a number of things. The next thing we want to do is wire up functionality to start and stop presentation of the WebGL content to the display.

Continuing on with the previous code block, we now add an event listener to our start/stop button (btn) — when this button is clicked we want to check whether we are presenting to the display already (we do this in a fairly dumb fashion, by checking what the button textContent contains).

If the display is not already presenting, we use the VRDisplay.requestPresent() (en-US) method to request that the browser start presenting content to the display. This takes as a parameter an array of the VRLayerInit (en-US) objects representing the layers you want to present in the display.

Since the maximum number of layers you can display is currently 1, and the only required object member is the VRLayerInit.source (en-US) property (which is a reference to the <canvas> you want to present in that layer; the other parameters are given sensible defaults — see leftBounds (en-US) and rightBounds (en-US))), the parameter is simply [{ source: canvas }].

requestPresent() returns a promise that is fulfilled when the presentation begins successfully.

// Starting the presentation when the button is clicked: It can only be called in response to a user gesture

btn.addEventListener('click', function() {

if(btn.textContent === 'Start VR display') {

vrDisplay.requestPresent([{ source: canvas }]).then(function() {

console.log('Presenting to WebVR display');

With our presentation request successful, we now want to start setting up to render content to present to the VRDisplay. First of all we set the canvas to the same size as the VR display area. We do this by getting the VREyeParameters (en-US) for both eyes using VRDisplay.getEyeParameters() (en-US).

We then do some simple math to calculate the total width of the VRDisplay rendering area based on the eye VREyeParameters.renderWidth (en-US) and VREyeParameters.renderHeight (en-US).

// Set the canvas size to the size of the vrDisplay viewport

var leftEye = vrDisplay.getEyeParameters("left");

var rightEye = vrDisplay.getEyeParameters("right");

canvas.width = Math.max(leftEye.renderWidth, rightEye.renderWidth) * 2;

canvas.height = Math.max(leftEye.renderHeight, rightEye.renderHeight);

Next, we cancel the animation loop previously set in motion by the Window.requestAnimationFrame() call inside the drawScene() function, and instead invoke drawVRScene(). This function renders the same scene as before, but with some special WebVR magic going on. The loop inside here is maintained by WebVR's special VRDisplay.requestAnimationFrame (en-US) method.

// stop the normal presentation, and start the vr presentation

window.cancelAnimationFrame(normalSceneFrame);

drawVRScene();

Finalmente, actualizamos el texto del botón para que la próxima vez que se presione, detenga la presentación en la pantalla VR.

btn.textContent = 'Exit VR display';

});

To stop the VR presentation when the button is subsequently pressed, we call VRDisplay.exitPresent() (en-US). We also reverse the button's text content, and swap over the requestAnimationFrame calls. You can see here that we are using VRDisplay.cancelAnimationFrame (en-US) to stop the VR rendering loop, and starting the normal rendering loop off again by calling drawScene().

} else {

vrDisplay.exitPresent();

console.log('Stopped presenting to WebVR display');

btn.textContent = 'Start VR display';

// Stop the VR presentation, and start the normal presentation

vrDisplay.cancelAnimationFrame(vrSceneFrame);

drawScene();

}

});

}

});

} else {

console.log('WebVR API not supported by this browser.');

}

}

}

Una vez iniciada la presentación, podrás ver la vista estereoscópica que se muestra en el navegador:

A continuación, aprenderá cómo se produce realmente la vista estereoscópica.

Why does WebVR have its own requestAnimationFrame()?

This is a good question. The reason is that for smooth rendering inside the VR display, you need to render the content at the display's native refresh rate, not that of the computer. VR display refresh rates are greater than PC refresh rates, typically up to 90fps. The rate will be differ from the computer's core refresh rate.

Note that when the VR display is not presenting, VRDisplay.requestAnimationFrame (en-US) runs identically to Window.requestAnimationFrame, so if you wanted, you could just use a single rendering loop, rather than the two we are using in our app. We have used two because we wanted to do slightly different things depending on whether the VR display is presenting or not, and keep things separated for ease of comprehension.

Rendering and display

At this point, we've seen all the code required to access the VR hardware, request that we present our scene to the hardware, and start running the rending loop. Let's now look at the code for the rendering loop, and explain how the WebVR-specific parts of it work.

First of all, we begin the definition of our rendering loop function — drawVRScene(). The first thing we do inside here is make a call to VRDisplay.requestAnimationFrame() (en-US) to keep the loop running after it has been called once (this occurred earlier on in our code when we started presenting to the VR display). This call is set as the value of the global vrSceneFrame variable, so we can cancel the loop with a call to VRDisplay.cancelAnimationFrame() (en-US) once we exit VR presenting.

function drawVRScene() {

// WebVR: Request the next frame of the animation

vrSceneFrame = vrDisplay.requestAnimationFrame(drawVRScene);

Next, we call VRDisplay.getFrameData() (en-US), passing it the name of the variable that we want to use to contain the frame data. We initialized this earlier on — frameData. After the call completes, this variable will contain the data need to render the next frame to the VR device, packaged up as a VRFrameData (en-US) object. This contains things like projection and view matrices for rendering the scene correctly for the left and right eye view, and the current VRPose (en-US) object, which contains data on the VR display such as orientation, position, etc.

This has to be called on every frame so the rendered view is always up-to-date.

// Populate frameData with the data of the next frame to display

vrDisplay.getFrameData(frameData);

Now we retrieve the current VRPose (en-US) from the VRFrameData.pose (en-US) property, store the position and orientation for use later on, and send the current pose to the pose stats box for display, if the poseStatsDisplayed variable is set to true.

// You can get the position, orientation, etc. of the display from the current frame's pose

var curFramePose = frameData.pose;

var curPos = curFramePose.position;

var curOrient = curFramePose.orientation;

if (poseStatsDisplayed) {

displayPoseStats(curFramePose);

}

We now clear the canvas before we start drawing on it, so that the next frame is clearly seen, and we don't also see previous rendered frames:

// Clear the canvas before we start drawing on it.

gl.clear(gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT | gl.DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT);

We now render the view for both the left and right eyes. First of all we need to create projection and view locations for use in the rendering. these are WebGLUniformLocation (en-US) objects, created using the WebGLRenderingContext.getUniformLocation() (en-US) method, passing it the shader program's identifier and an identifying name as parameters.

// WebVR: Create the required projection and view matrix locations needed

// for passing into the uniformMatrix4fv methods below

var projectionMatrixLocation = gl.getUniformLocation(

shaderProgram,

"projMatrix",

);

var viewMatrixLocation = gl.getUniformLocation(shaderProgram, "viewMatrix");

The next rendering step involves:

- Specifying the viewport size for the left eye, using

WebGLRenderingContext.viewport(en-US) — this is logically the first half of the canvas width, and the full canvas height. - Specifying the view and projection matrix values to use to render the left eye — this is done using the

WebGLRenderingContext.uniformMatrix4fv(en-US) method, which is passed the location values we retrieved above, and the left matrices obtained from theVRFrameData(en-US) object. - Running the

drawGeometry()function, which renders the actual scene — because of what we specified in the previous two steps, we will render it for the left eye only.

// WebVR: Render the left eye’s view to the left half of the canvas

gl.viewport(0, 0, canvas.width * 0.5, canvas.height);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(

projectionMatrixLocation,

false,

frameData.leftProjectionMatrix,

);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(viewMatrixLocation, false, frameData.leftViewMatrix);

drawGeometry();

We now do exactly the same thing, but for the right eye:

// WebVR: Render the right eye’s view to the right half of the canvas

gl.viewport(canvas.width * 0.5, 0, canvas.width * 0.5, canvas.height);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(

projectionMatrixLocation,

false,

frameData.rightProjectionMatrix,

);

gl.uniformMatrix4fv(viewMatrixLocation, false, frameData.rightViewMatrix);

drawGeometry();

Next we define our drawGeometry() function. Most of this is just general WebGL code required to draw our 3D cube. You'll see some WebVR-specific parts in the mvTranslate() and mvRotate() function calls — these pass matrices into the WebGL program that define the translation and rotation of the cube for the current frame

You'll see that we are modifying these values by the position (curPos) and orientation (curOrient) of the VR display we got from the VRPose (en-US) object. The result is that, for example, as you move or rotate your head left, the x position value (curPos[0]) and y rotation value ([curOrient[1]) are added to the x translation value, meaning that the cube will move to the right, as you'd expect when you are looking at something and then move/turn your head left.

This is a quick and dirty way to use VR pose data, but it illustrates the basic principle.

function drawGeometry() {

// Establish the perspective with which we want to view the

// scene. Our field of view is 45 degrees, with a width/height

// ratio of 640:480, and we only want to see objects between 0.1 units

// and 100 units away from the camera.

perspectiveMatrix = makePerspective(45, 640.0 / 480.0, 0.1, 100.0);

// Set the drawing position to the "identity" point, which is

// the center of the scene.

loadIdentity();

// Now move the drawing position a bit to where we want to start

// drawing the cube.

mvTranslate([

0.0 - curPos[0] * 25 + curOrient[1] * 25,

5.0 - curPos[1] * 25 - curOrient[0] * 25,

-15.0 - curPos[2] * 25,

]);

// Save the current matrix, then rotate before we draw.

mvPushMatrix();

mvRotate(cubeRotation, [0.25, 0, 0.25 - curOrient[2] * 0.5]);

// Draw the cube by binding the array buffer to the cube's vertices

// array, setting attributes, and pushing it to GL.

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, cubeVerticesBuffer);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(vertexPositionAttribute, 3, gl.FLOAT, false, 0, 0);

// Set the texture coordinates attribute for the vertices.

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ARRAY_BUFFER, cubeVerticesTextureCoordBuffer);

gl.vertexAttribPointer(textureCoordAttribute, 2, gl.FLOAT, false, 0, 0);

// Specify the texture to map onto the faces.

gl.activeTexture(gl.TEXTURE0);

gl.bindTexture(gl.TEXTURE_2D, cubeTexture);

gl.uniform1i(gl.getUniformLocation(shaderProgram, "uSampler"), 0);

// Draw the cube.

gl.bindBuffer(gl.ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, cubeVerticesIndexBuffer);

setMatrixUniforms();

gl.drawElements(gl.TRIANGLES, 36, gl.UNSIGNED_SHORT, 0);

// Restore the original matrix

mvPopMatrix();

}

The next bit of the code has nothing to do with WebVR — it just updates the rotation of the cube on each frame:

// Update the rotation for the next draw, if it's time to do so.

var currentTime = new Date().getTime();

if (lastCubeUpdateTime) {

var delta = currentTime - lastCubeUpdateTime;

cubeRotation += (30 * delta) / 1000.0;

}

lastCubeUpdateTime = currentTime;

The last part of the rendering loop involves us calling VRDisplay.submitFrame() (en-US) — now all the work has been done and we've rendered the display on the <canvas>, this method then submits the frame to the VR display so it is displayed on there as well.

// WebVR: Indicate that we are ready to present the rendered frame to the VR display

vrDisplay.submitFrame();

}

Displaying the pose (position, orientation, etc.) data

In this section we'll discuss the displayPoseStats() function, which displays our updated pose data on each frame. The function is fairly simple.

First of all, we store the six different property values obtainable from the VRPose (en-US) object in their own variables — each one is a Float32Array (en-US).

function displayPoseStats(pose) {

var pos = pose.position;

var orient = pose.orientation;

var linVel = pose.linearVelocity;

var linAcc = pose.linearAcceleration;

var angVel = pose.angularVelocity;

var angAcc = pose.angularAcceleration;

We then write out the data into the information box, updating it on every frame. We've clamped each value to three decimal places using toFixed(), as the values are hard to read otherwise.

You should note that we've used a conditional expression to detect whether the linear acceleration and angular acceleration arrays are successfully returned before we display the data. These values are not reported by most VR hardware as yet, so the code would throw an error if we did not do this (the arrays return null if they are not successfully reported).

posStats.textContent = 'Position: x ' + pos[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + pos[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + pos[2].toFixed(3);

orientStats.textContent = 'Orientation: x ' + orient[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + orient[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + orient[2].toFixed(3);

linVelStats.textContent = 'Linear velocity: x ' + linVel[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + linVel[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + linVel[2].toFixed(3);

angVelStats.textContent = 'Angular velocity: x ' + angVel[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + angVel[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + angVel[2].toFixed(3);

if(linAcc) {

linAccStats.textContent = 'Linear acceleration: x ' + linAcc[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + linAcc[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + linAcc[2].toFixed(3);

} else {

linAccStats.textContent = 'Linear acceleration not reported';

}

if(angAcc) {

angAccStats.textContent = 'Angular acceleration: x ' + angAcc[0].toFixed(3) + ', y ' + angAcc[1].toFixed(3) + ', z ' + angAcc[2].toFixed(3);

} else {

angAccStats.textContent = 'Angular acceleration not reported';

}

}

WebVR events

The WebVR spec features a number of events that are fired, allowing our app code to react to changes in the state of the VR display (see Window events). For example:

vrdisplaypresentchange— Fires when the presenting state of a VR display changes — i.e. goes from presenting to not presenting, or vice versa.vrdisplayconnect— Fires when a compatible VR display has been connected to the computer.vrdisplaydisconnect— Fires when a compatible VR display has been disconnected from the computer.

To demonstrate how they work, our simple demo includes the following example:

window.addEventListener("vrdisplaypresentchange", function (e) {

console.log(

"Display " +

e.display.displayId +

" presentation has changed. Reason given: " +

e.reason +

".",

);

});

As you can see, the event object (en-US) provides two useful properties — VRDisplayEvent.display (en-US), which contains a reference to the VRDisplay (en-US) the event was fired in response to, and VRDisplayEvent.reason (en-US), which contains a human-readable reason why the event was fired.

This is a very useful event; you could use it to handle cases where the display gets disconnected unexpectedly, stopping errors from being thrown and making sure the user is aware of the situation. In Google's Webvr.info presentation demo, the event is used to run an onVRPresentChange() function, which updates the UI controls as appropriate and resizes the canvas.

Summary

This article has given you the very basics of how to create a simple WebVR 1.1 app, to help you get started.