Introdução às Web APIs

Primeiro, vamos ver as APIs a partir de um nível mais alto: o que são, como funcionam, como usá-las em seu código e como são estruturadas? Ainda, vamos entender quais são as principais classes de APIs e quais usos elas possuem.

| Pré-requisitos: |

Conhecimentos básicos de computação, HTML, CSS e JavaScript (veja primeiros passos, elementos construtivos e introdução a objetos). |

|---|---|

| Objetivo: | Familiarizar-se com APIs, o que elas podem fazer, e como usá-las em seu código. |

O que são APIs?

As APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) são construções disponíveis nas linguagens de programação que permitem a desenvolvedores criar funcionalidades complexas mais facilmente. Tais construções abstraem o código mais complexo, proporcionando o uso de sintaxes mais simples em seu lugar.

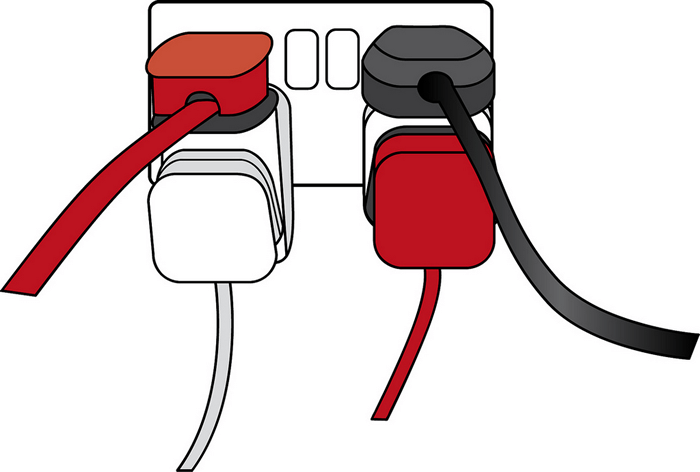

Pense no seguinte exemplo: o uso de energia elétrica em sua casa ou apartamento. Quando você deseja utilizar um eletrodoméstico, você precisa somente ligar o aparelho na tomada. Não é preciso conectar diretamente o fio do aparelho diretamente na caixa de luz. Isso seria, além de muito ineficiente, difícil e perigoso de ser feito (caso você não seja eletricista).

Fonte da imagem: Overloaded plug socket por The Clear Communication People, retirado do Flickr.

Da mesma forma, caso você queira programar gráficos em 3D, é muito mais fácil usar uma API escrita em linguagem de alto nível como JavaScript ou Python, do que escrever em código de mais baixo nível (C ou C++) que controla diretamente a GPU ou outras funções gráficas.

Nota: para mais informações, consulte o termo API no glossário.

APIs JavaScript client-side

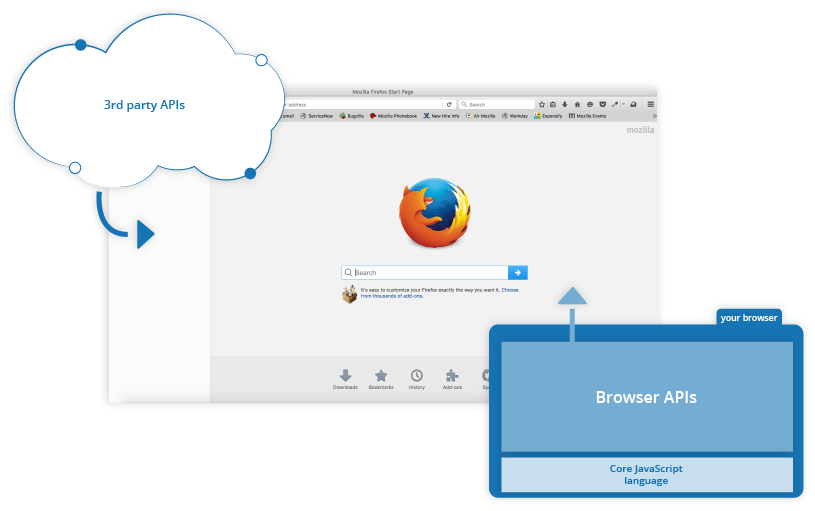

A linguagem JavaScript, especialmente client-side, possui diversas APIs disponíveis. Elas não fazem parte da linguagem em si, mas são escritas sobre o core da linguagem JavaScript, fornecendo superpoderes para serem utilizados em seu código. Geralmente, tais APIs fazem parte de uma das seguintes categorias:

- APIs de navegadores: fazem parte do seu navegador web, sendo capazes de expor dados do navegador e do ambiente ao redor do computador circundante, além de fazer coisas úteis com esses dados. Por exemplo, a API Web Áudio fornece construções JavaScript simples para manipular áudio em seu navegador - pegar uma faixa de áudio, alterar o volume dela, aplicar efeitos, etc. Por trás dos panos, o navegador utiliza códigos complexos de baixo nível (ex: C++) para realizar o processamento de áudio de fato. Como foi dito anteriormente, essa complexidade toda é abstraída de você pela API.

- APIs de terceiros: geralmente, não fazem parte do navegador e você precisa recuperar seu código e suas informações de outro local da web. A API do Twitter, por exemplo, permite mostrar os seus últimos tweets no seu site. Ela fornece um conjunto de construções especiais para ser usado de maneira a consultar o serviço do Twitter e retornar informações específicas.

Relacionamento entre JavaScript, APIs, e outras ferramentas JavaScript

Na seção anterior, abordamos as APIs JavaScript client-side e como elas se relacionam com a linguagem JavaScript. Esse ponto merece uma revisão e também uma breve menção de como outras ferramentas JavaScript encaixam-se nesse contexto:

- JavaScript — linguagem de alto nível, embutida em navegadores, que permite implementar funcionalidades em páginas web/aplicativos. A linguagem também está disponível em outros ambientes de programação, tais como o Node.

- APIs de navegadores — construções presentes no navegador, as quais são baseadas em linguagem JavaScript e permitem a implementação de funcionalidades de uma maneira mais fácil.

- APIs de terceiros — construções presentes em plataformas de terceiros (ex: Twitter, Facebook), que permitem o uso de alguma funcionalidade da plataforma em suas páginas na web. Um exemplo é a possibilidade de mostrar os últimos tweets em sua página.

- Bibliotecas JavaScript — em geral, um ou mais arquivos JavaScript contendo funções personalizadas, as quais podem ser usadas em sua página web para acelerar ou permitir escrever funcionalidades comuns. Exemplos: jQuery, Mootools e React.

- Frameworks JavaScript — uma evolução das bibliotecas. Frameworks JavaScript (ex: Angular e Ember), normalmente, são pacotes de tecnologias HTML, CSS, JavaScript e outras, que você instala e usa para escrever uma aplicação web completa do zero. A principal diferença entre uma biblioteca e um framework é a inversão de controle ("Inversion of Control"). Quando um método de uma biblioteca é chamado, a pessoa desenvolvedora está no controle. Em um framework, o controle inverte-se: é o framework que chama o código da pessoa desenvolvedora.

O que as APIs podem fazer?

Existem muitas APIs disponíveis, nos navegadores modernos, que permitem uma liberdade de ação na hora de codar. Você pode conferir isso na página de referência das APIs da MDN.

APIs comuns de navegadores

As categorias mais comuns de APIs de navegadores que você irá utilizar (e que veremos em detalhes neste módulo), são:

- APIs para manipular documentos carregados no navegador. O exemplo mais óbvio é a API DOM (Document Object Model), que permite manipular HTML e CSS — criando, removendo a alterando o HTML, aplicando dinamicamente novos estilos a sua página, etc. Toda vez que você vê uma janela pop-up em uma página, ou um novo conteúdo é mostrado, o DOM está em ação. Para saber mais sobre estes tipos de API, leia Manipulando documentos.

- APIs que buscam dados no servidor para atualizar pequenas seções da página, por conta própria, são bastante usadas. Isso, a princípio, parece ser um detalhe pequeno, mas tem um impacto enorme na performance e no comportamento dos sites. Se você precisa atualizar a cotação de uma ação ou listar novas histórias disponíveis, a possibilidade de fazer isso instantaneamente sem precisar atualizar a página dá a impressão de um site muito mais responsivo. Entre as APIs que tornam isso possível, podemos destacar o

XMLHttpRequeste a API Fetch. Você pode também encontrar o termo Ajax, que descreve essa técnica. Para saber mais sobre essas APIs, leia Fetching data from the server. - APIs para desenhar e manipular elementos gráficos são completamente suportados nos browsers — os mais comuns são Canvas e WebGL, que possibilitam que você atualize os dados dos pixels em um elemento HTML de maneira programática.

<canvas>elemento para criar cenas 2d e 3d. Por exemplo, você poderia dezenhar formas como retangulos e circulos, importar uma imagem para o canvas, e aplicar um filtro para sepia ou grayscale usando o Canvas API, ou criar uma complexa cena 3d com brilho e texturas usando WebGL. Essas APIs são frequentemente combinar com APIs para criar loops de animações(comowindow.requestAnimationFrame()) e outros para constantemente lançar cenas like como cartoons e jogos. - Audio and Video APIs como

HTMLMediaElement(en-US), a Web Audio API, e WebRTC permiten a você fazer coisas realmente interessantes com multimedia como a criação personalizada controles de UI para executar audio e video, exibindo faixas de texto como legendas e legendas ocultas junto com seus vídeos, capturando vídeo de sua câmera da web para ser manipulado por meio de uma tela (veja acima) ou exibido no computador de outra pessoa em uma webconferência,ou adicionar efeitos às trilhas de áudio (como ganho, distorção, panorâmica, etc.). - Device APIs São basicamente APIs para manipulação e recuperação de dados de hardware de dispositivo moderno de uma forma que seja útil para aplicativos da web.Já falamos sobre a Geolocation API acessando o dispositivo dados de localização para que você possa marcar sua posição em um mapa.Outros exemplos incluem informar ao usuário que uma atualização útil está disponível em um aplicativo da web por meio de notificações do sistema(Veja em Notifications API (en-US))ou hardware de vibração(Veja em Vibration API (en-US)).

- Client-side storage APIs estão se tornando muito mais difundidos em navegadores da web - a capacidade de armazenar dados no lado do cliente é muito útil se você quer criar um app que vai salvar seu estado entre carregamentos de página, e talvez até funcione quando o dispositivo estiver offline. Existem várias opções disponíveis, por exemplo, armazenamento simples de nome / valor com o Web Storage API, e armazenamento de dados tabulares mais complexos com o IndexedDB API.

APIs comuns de terceiros

APIs de terceiros são bastante variadas. Dentre as mais populares, que você eventualmente irá utilizar em algum momento, podermos destacar:

- A Twitter API, que permite coisas como mostrar seu últimos tweets no seu website.

- O Google Maps API permite que você faça todo tipo de coisa com mapas nas suas páginas web (funnily enough, it also powers Google Maps). This is now an entire suite of APIs, which handle a wide variety of tasks, as evidenced by the Google Maps API Picker.

- The Facebook suite of APIs enables you to use various parts of the Facebook ecosystem to benefit your app, for example by providing app login using Facebook login, accepting in-app payments, rolling out targetted ad campaigns, etc.

- The YouTube API, which allows you to embed YouTube videos on your site, search YouTube, build playlists, and more.

- The Twilio API, which provides a framework for building voice and video call functionality into your app, sending SMS/MMS from your apps, and more.

Nota: Você pode encontrar informações sobre muitas outras APIs de terceiros no Programmable Web API directory.

Como as APIs funcionam?

APIs JavaScript possuem pequenas diferenças mas, em geral, possuem funcionalidades em comum e operam de maneira semelhante.

Elas são baseadas em objetos

Your code interacts with APIs using one or more JavaScript objects, which serve as containers for the data the API uses (contained in object properties), and the functionality the API makes available (contained in object methods).

Nota: If you are not already familiar with how objects work, you should go back and work through our JavaScript objects module before continuing.

Let's return to the example of the Geolocation API — this is a very simple API that consists of a few simple objects:

Geolocation, which contains three methods for controlling the retrieval of geodata.Position, which represents the position of a device at a given time — this contains aCoordinatesobject that contains the actual position information, plus a timestamp representing the given time.Coordinates, which contains a whole lot of useful data on the device position, including latitude and longitude, altitude, velocity and direction of movement, and more.

So how do these objects interact? If you look at our maps-example.html example (see it live also), you'll see the following code:

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(function (position) {

var latlng = new google.maps.LatLng(

position.coords.latitude,

position.coords.longitude,

);

var myOptions = {

zoom: 8,

center: latlng,

mapTypeId: google.maps.MapTypeId.TERRAIN,

disableDefaultUI: true,

};

var map = new google.maps.Map(

document.querySelector("#map_canvas"),

myOptions,

);

});

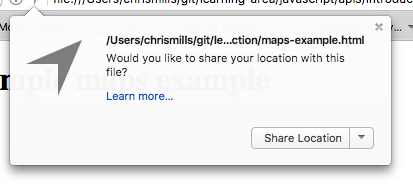

Nota: When you first load up the above example, you should be given a dialog box asking if you are happy to share your location with this application (see the They have additional security mechanisms where appropriate section later in the article). You need to agree to this to be able to plot your location on the map. If you still can't see the map, you may need to set your permissions manually; you can do this in various ways depending on what browser you are using; for example in Firefox go to > Tools > Page Info > Permissions, then change the setting for Share Location; in Chrome go to Settings > Privacy > Show advanced settings > Content settings then change the settings for Location.

We first want to use the Geolocation.getCurrentPosition() method to return the current location of our device. The browser's Geolocation object is accessed by calling the Navigator.geolocation property, so we start off by using

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(function(position) { ... });

Isso é equivalente a fazer algo como

var myGeo = navigator.geolocation;

myGeo.getCurrentPosition(function(position) { ... });

But we can use the dot syntax to chain our property/method access together, reducing the number of lines we have to write.

The Geolocation.getCurrentPosition() method only has a single mandatory parameter, which is an anonymous function that will run when the device's current position has been successfully retrieved. This function itself has a parameter, which contains a Position object representing the current position data.

Nota: A function that is taken by another function as an argument is called a callback function.

This pattern of invoking a function only when an operation has been completed is very common in JavaScript APIs — making sure one operation has completed before trying to use the data the operation returns in another operation. These are called asynchronous operations. Because getting the device's current position relies on an external component (the device's GPS or other geolocation hardware), we can't guarantee that it will be done in time to just immediately use the data it returns. Therefore, something like this wouldn't work:

var position = navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition();

var myLatitude = position.coords.latitude;

If the first line had not yet returned its result, the second line would throw an error, because the position data would not yet be available. For this reason, APIs involving asynchronous operations are designed to use callback functions, or the more modern system of Promises, which were made available in ECMAScript 6 and are widely used in newer APIs.

We are combining the Geolocation API with a third party API — the Google Maps API — which we are using to plot the location returned by getCurrentPosition() on a Google Map. We make this API available on our page by linking to it — you'll find this line in the HTML:

<script

type="text/javascript"

src="https://maps.google.com/maps/api/js?key=AIzaSyDDuGt0E5IEGkcE6ZfrKfUtE9Ko_de66pA"></script>

To use the API, we first create a LatLng object instance using the google.maps.LatLng() constructor, which takes our geolocated Coordinates.latitude (en-US) and Coordinates.longitude (en-US) values as parameters:

var latlng = new google.maps.LatLng(

position.coords.latitude,

position.coords.longitude,

);

This object is itself set as the value of the center property of an options object that we've called myOptions. We then create an object instance to represent our map by calling the google.maps.Map() constructor, passing it two parameters — a reference to the <div> element we want to render the map on (with an ID of map_canvas), and the options object we defined just above it.

var myOptions = {

zoom: 8,

center: latlng,

mapTypeId: google.maps.MapTypeId.TERRAIN,

disableDefaultUI: true,

};

var map = new google.maps.Map(document.querySelector("#map_canvas"), myOptions);

With this done, our map now renders.

This last block of code highlights two common patterns you'll see across many APIs. First of all, API objects commonly contain constructors, which are invoked to create instances of those objects that you'll use to write your program. Second, API objects often have several options available that can be tweaked to get the exact environment you want for your program. API constructors commonly accept options objects as parameters, which is where you'd set such options.

Nota: Don't worry if you don't understand all the details of this example immediately. We'll cover using third party APIs in a lot more detail in a future article.

Possuem pontos de entrada reconhecíveis

When using an API, you should make sure you know where the entry point is for the API. In The Geolocation API, this is pretty simple — it is the Navigator.geolocation property, which returns the browser's Geolocation object that all the useful geolocation methods are available inside.

The Document Object Model (DOM) API has an even simpler entry point — its features tend to be found hanging off the Document object, or an instance of an HTML element that you want to affect in some way, for example:

var em = document.createElement("em"); // create a new em element

var para = document.querySelector("p"); // reference an existing p element

em.textContent = "Hello there!"; // give em some text content

para.appendChild(em); // embed em inside para

Other APIs have slightly more complex entry points, often involving creating a specific context for the API code to be written in. For example, the Canvas API's context object is created by getting a reference to the <canvas> element you want to draw on, and then calling its HTMLCanvasElement.getContext() method:

var canvas = document.querySelector("canvas");

var ctx = canvas.getContext("2d");

Anything that we want to do to the canvas is then achieved by calling properties and methods of the content object (which is an instance of CanvasRenderingContext2D), for example:

Ball.prototype.draw = function () {

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.fillStyle = this.color;

ctx.arc(this.x, this.y, this.size, 0, 2 * Math.PI);

ctx.fill();

};

Nota: You can see this code in action in our bouncing balls demo (see it running live also).

Usam eventos para lidar com mudanças de estado

We already discussed events earlier on in the course, in our Introduction to events article — this article looks in detail at what client-side web events are and how they are used in your code. If you are not already familiar with how client-side web API events work, you should go and read this article first before continuing.

Some web APIs contain no events, but some contain a number of events. The handler properties that allow us to run functions when events fire are generally listed in our reference material in separate "Event handlers" sections. As a simple example, instances of the XMLHttpRequest object (each one represents an HTTP request to the server to retrieve a new resource of some kind) have a number of events available on them, for example the load event is fired when a response has been successfully returned containing the requested resource, and it is now available.

O código seguinte fornece um exemplo simples de como isso seria utilizado:

var requestURL =

"https://mdn.github.io/learning-area/javascript/oojs/json/superheroes.json";

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open("GET", requestURL);

request.responseType = "json";

request.send();

request.onload = function () {

var superHeroes = request.response;

populateHeader(superHeroes);

showHeroes(superHeroes);

};

Nota: You can see this code in action in our ajax.html example (see it live also).

The first five lines specify the location of resource we want to fetch, create a new instance of a request object using the XMLHttpRequest() constructor, open an HTTP GET request to retrieve the specified resource, specify that the response should be sent in JSON format, then send the request.

The onload handler function then specifies what we do with the response. We know the response will be successfully returned and available after the load event has required (unless an error occurred), so we save the response containing the returned JSON in the superHeroes variable, then pass it to two different functions for further processing.

Possuem mecanismos de segurança adicionais, quando apropriado

WebAPI features are subject to the same security considerations as JavaScript and other web technologies (for example same-origin policy (en-US)), but they sometimes have additional security mechanisms in place. For example, some of the more modern WebAPIs will only work on pages served over HTTPS due to them transmitting potentially sensitive data (examples include Service Workers and Push).

In addition, some WebAPIs request permission to be enabled from the user once calls to them are made in your code. As an example, you may have noticed a dialog like the following when loading up our earlier Geolocation example:

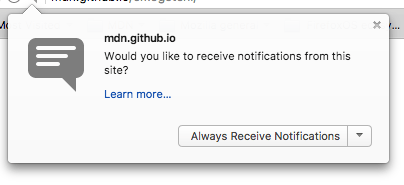

The Notifications API (en-US) asks for permission in a similar fashion:

These permission prompts are given to users for security — if they weren't in place, then sites could start secretly tracking your location without you knowing it, or spamming you with a lot of annoying notifications.

Resumo

Ao chegar aqui, você deve ter uma boa ideia do que são APIs, como funcionam e o que você pode fazer com elas em seu código JavaScript. Além do mais, você deve estar ansioso(a) para colocar a mão na massa e trabalhar com APIs. Na sequência, iremos ver como manipular documentos com o DOM (Document Object Model).